Beauty, understood as both a concept and a representation, has occupied a central role in art since its very beginnings. From Plato’s thesis that art’s function is to reflect an ideal world, to Renaissance theories of divine proportion, beauty was once considered the very purpose of art itself. Over time, however, the perspective on such “ideal” narrowed, becoming intertwined with the female body. Its representations were rarely neutral, as they were constructed and visualised by those with the power to define it. Ever morphing to reflect the evolving standards of society, and encouraging conformity, the construct of beauty became a vehicle for the demands and expectations of the male gaze.

Sylvia Sleigh, a pioneering feminist painter and key figure in the LYRA Collection, turns the legacy of exploitative objectification inside out. Her work, rooted in the Women’s Art Movement of the 1970s, draws from the classical compositions but inverts the power dynamics, where male figures occupy poses stereotypically associated with female models. Sleigh does not reject the nude form, nor does she erase the beauty. Instead, beauty is seen anew, namely through care, equality and the refusal to flatten a person into an image.

In opposition to grand and universal ideals, for Sleigh, beauty is something deeply personal. The artist’s subjects are empowered through their individualism, their psychological presence and agency seeping through the canvas.

Cloud Hill, by Anna Weyant, LYRA Collection.

Courtesy, LYRA Collection

With a similar poetry of treasuring the individual behind the body, LYRA artist Anna Weyant portrays female figures in tender and at once tragicomic scenes. Staying true to the human condition of inconsistencies and idiosyncrasies, Weyant’s visual language reconstructs societal, art historical, and cinematic signifiers of femininity. Under the veil of dreamline mystery and dark humour of her compositions, the artist’s subjects remain unapologetically true to themselves, with all the human complexities and contradictions that beauty entails. Once the concept of beauty is revealed to be a concept – a constructed idea at the mercy of those with the power to determine its parameters – its foundations begin to crumble. As the constructions of what it means to be beautiful begin to be dismantled, beauty becomes an unfixed, inclusive, and shapeshifting word that celebrates one’s identity.

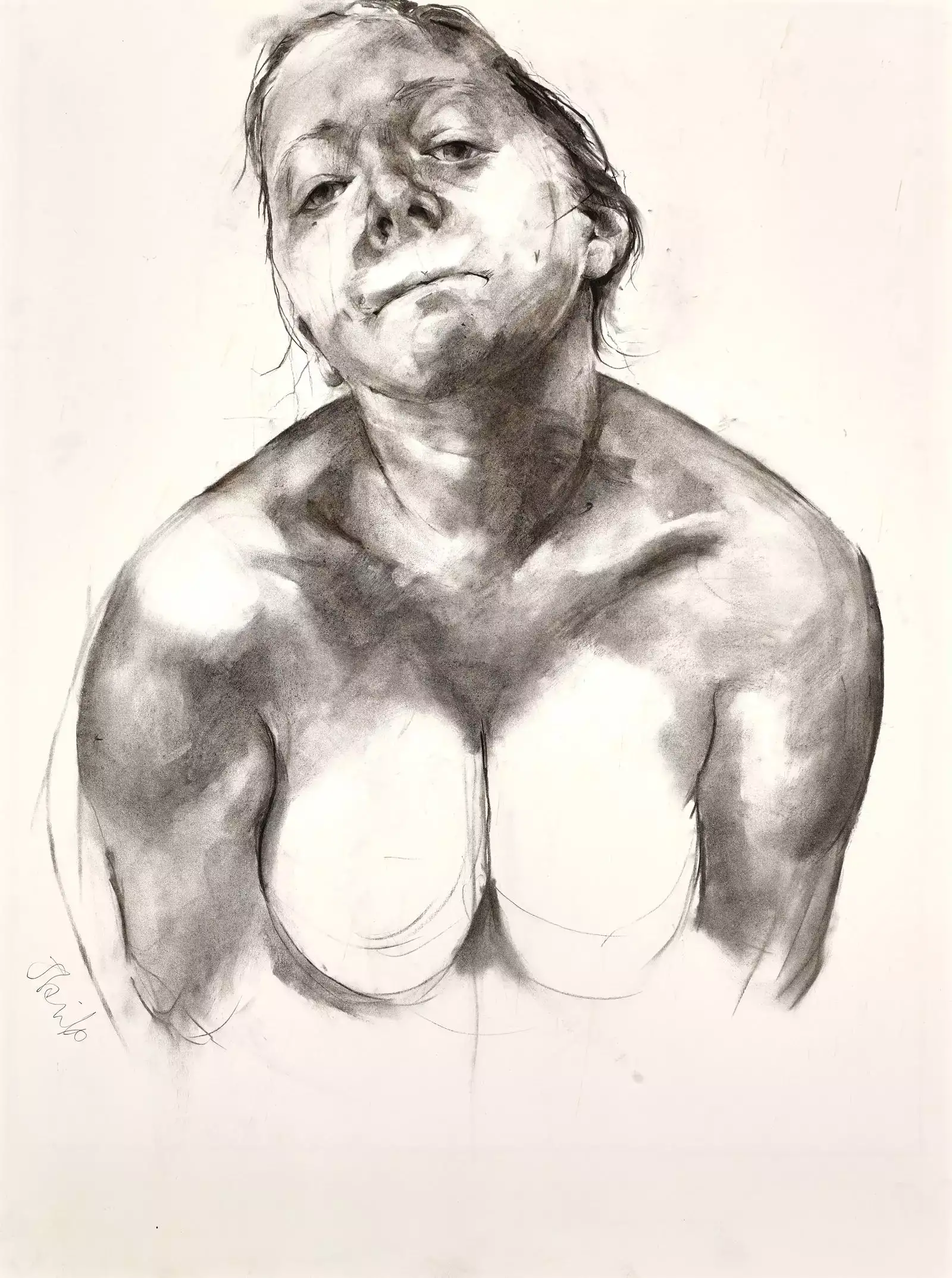

Self Portrait, by Jenny Saville, LYRA Collection

Courtesy, LYRA Collection

Since antiquity, the human figure has been a battleground for ideals. As seen in Greek sculptures seemingly struck by divine symmetry, Botticelli’s ethereal women, the sensual bodies in Ruben’s compositions, or Ingres’s porcelain-skinned odalisques, beauty in Western art is commonly synonymous with harmony, proportion, and control. The “perfect” body was sleek, smooth, and often female, there to be admired, but never lived in.

LYRA artist Jenny Saville dismantles this art historical heritage with brutal honesty and painterly force. Her large-scale paintings confront us with bodies as they are: marked by time, weight, gender, trauma, and transformation. Echoing feminist theorists such as Luce Irigaray and Julia Kristeva, Saville challenges the language of the gaze and the gendered coding of representation. Refusing to conform to any classical notions of what is ideal, beautiful, and, in other words, passive, the artist reframes beauty into an embodiment of the living, the visceral, and the real.

Bunny Gets Snookered #8, by Sarah Lucas, LYRA Collection.

Courtesy, LYRA Collection

In the work of a fellow member of the Young British Artist movement in the LYRA collection, beauty is confrontational. Gender norms at her disposal, Sarah Lucas is an artist whose irony and humour single-handedly – but with an arm that is actually a bunny ear – disrupt societal conventions of gender, sex, and desire. Lucas liberates the body through the grotesque, to the extent that the body sometimes becomes bodiless; in its place is freedom, and in that freedom, a kind of uncanny joy.

The multiplicity of emotional and physiological states Lucas evokes brings forth a kind of realness, despite how surreal the tangles of stuffed-stocking breasts or twisted nylon limbs appear to be. Resisting dominant aesthetic norms, which are deeply complicit in containing beauty within a narrow, sanitised ideal, Lucas turns the abject into a site of power, making a case for beauty as something unruly, strange, and misfitting. In her vocabulary of the familiar and the everyday, beauty is not fixed to a singular form, gender, or body. Instead, it emerges in the unexpected, the excessive, and the raw, a place where discomfort and delight collide.

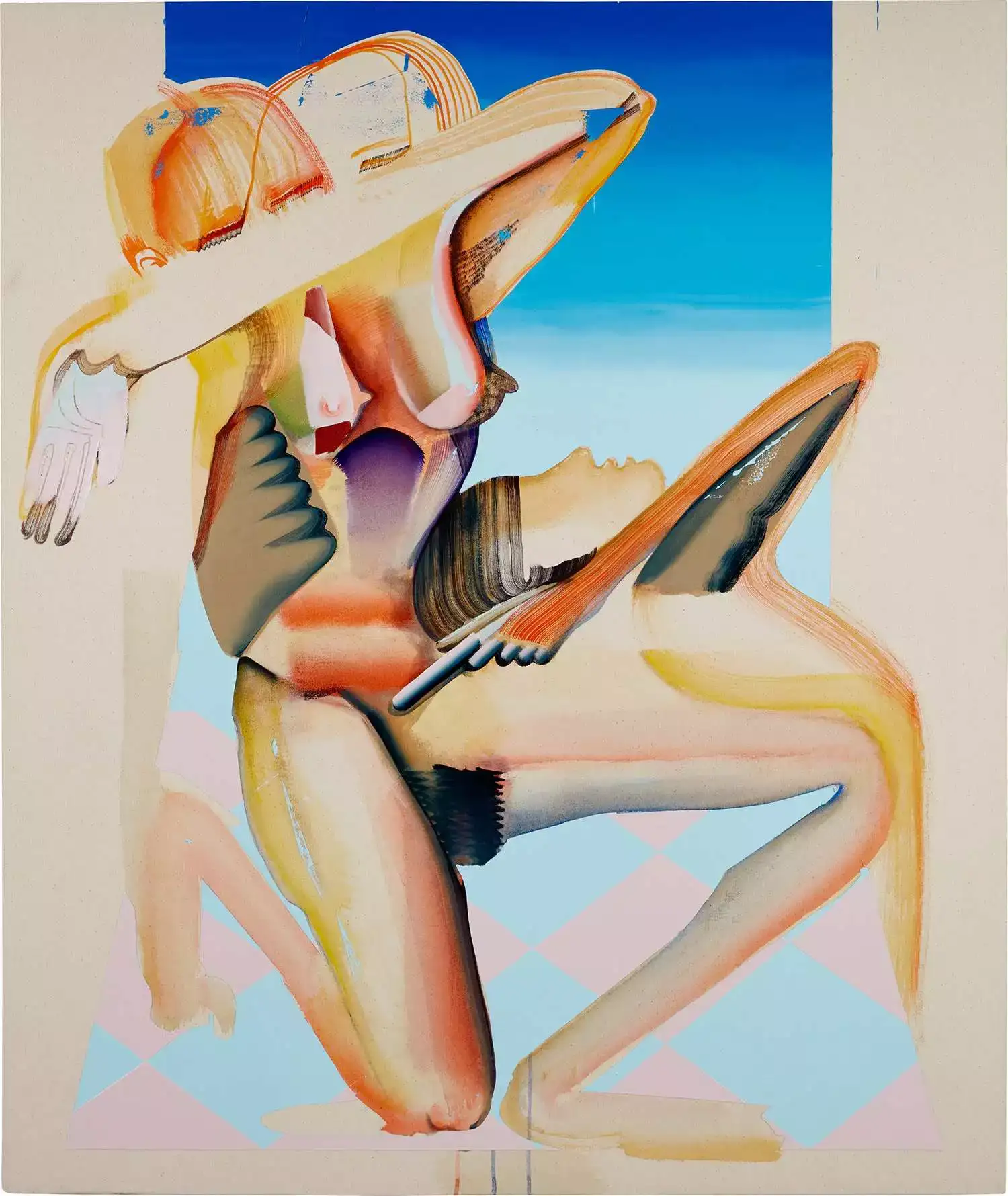

Our Eyes Our Open/Are Eyes Are Open, by Christina Quarles, LYRA Collection.

Courtesy, LYRA Collection

If past ideals of beauty sought clarity and fixed identity, LYRA artist Christina Quarles paints in refusal of both, creating work that breaks from classical form entirely. Her overlapping, fragmented and tangled figures resist categorisation, a tool once comfortably employed by Western-centric, masculine, and hegemonic frameworks to define what the world is and how it functions. Instead, in Quarles’s work, bodies blur gender, race, and selfhood; figures twist and merge into one another, at once visible and obscured.

Undoing Renaissance beauty that praised balance, proportion and a singular – and also stable, fixed, gendered and racialised – idea of beauty, Quarles’ compositions are disorienting and open-ended. The artist’s figures twist and merge into each other, at once visible and obscured. This visual language mirrors the complexity of Quarles’ own identity as a queer, mixed-race woman who lives in the US.

Historically, beauty in Western art has been tied to readability: you knew what you were seeing, and that it conformed to known ideals. But in Quarles’ work, ambiguity and multiplicity become forms of resistance: in place of abstract ideals comes the real experience of inhabiting your own body in a world of projection and misrecognition, within art history and far beyond it.

Each in her own way and own visual and artistic language, Sleigh, Weyant, Saville, Lucas and Quarles speak to a shared movement towards liberating beauty from the narrow illusion of perfection that runs through art history on repeat. To break through this illusion does not mean to relocate beauty into another grand or monumental fixture. Instead, the focus shifts onto the individual, the living, the unfixed and the imperfect, where the kind of beauty that may be closest to the universal resides.